I began my career as a waiter, which I would not wish on anyone. I don’t know how many times I heard a customer say “Here’s your tip: buy low, sell high.” As a waiter, the correct response is to laugh as if you’ve never heard that one before and suggest that the customer consider being a stand-up comedian. If you happen to be a restaurant patron who still uses that joke…stop it!

As tired as the joke is, and as obvious as the rule is when applied to stocks, there is still some insight that can be squeezed out of this phrase for those who trade options. Whether you’re trading straight Calls and Puts, Covered Calls, Iron Condors, or Broken-Wing Butterflies With Chipped Teeth, it is still important to buy low and sell high, but the rule may have nothing to do with the price of the underlying stock.

Anatomy of an Option Trade

Every trade involving options has several parameters that need to be considered, known as “the Greeks.” The major Greeks are Delta, Theta, and Vega. Gamma is also an important parameter, but not in terms of helping me get to the main point of this article, which is Vega. The parameter every investor deals with, whether they know it or not, is Delta, which measures a stock and/or option position’s sensitivity to stock price movements.

A Delta value of 100 means that the overall position will gain $100 for each $1 gain in the underlying stock price. It’s pretty easy to establish a position with 100 Delta…you can simply buy 100 shares of stock. Options have a Delta value as well. For example, an at-the-money Call contract has a Delta of +50, and an at-the-money Put contract has a Delta of -50. In other words, an at-the-money Put contract will gain $50 for each $1 drop in the stock price (and lose $50 for each $1 gain in stock price).

Theta and Vega are also pretty straightforward. Theta is simply a measure of the amount of time value that is lost or gained per day from options, and Vega reflects the amount gained or lost from a 1% gain in Implied Volatility.

![]()

Buying Low and Selling High

If you believe a stock price is currently low and will be going higher, you would want to increase a position’s Delta. This is easy to do by simply buying stock. If you believe a stock’s Volatility is low and going higher, you would want to increase the position’s Vega. Since this can only be done by purchasing options it gets a little more complicated, due to the fact that buying options also changes Delta. In fact, if you purchased 1000 shares of stock (1000 Delta) and purchased 20 at-the-money Put contracts (each with a Delta of -50), the Deltas cancel each other out and you end of up with a position having a Delta of zero but plenty of Vega. If you want even more Vega, you can replace the 1000 shares of stock with 20 at-the-money Calls. The Delta of the resulting straddle position is still zero, but with twice the Vega and, unfortunately, twice the time decay (or Theta).

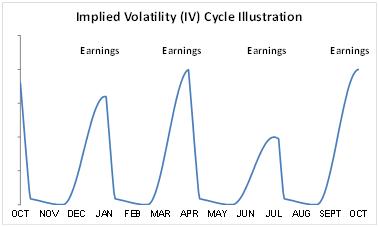

What’s thought of as “stock market timing” is really a matter of increasing and decreasing Delta at the right times. Because stocks seem to move in a relatively random manner, this is extremely hard to do unless you simply convince yourself that stocks always move higher. Volatility (or more accurately, Implied Volatility) on the other hand often follows a fairly regular pattern with a strong tendency to return to the mean. For many stocks, the release of earnings every three months provides enough of a catalyst to drive volatility higher for a number of days or several weeks prior to earnings, with a subsequent volatility crush immediately following the announcement.

This can provide a much more predictable pattern of lows and highs, as opposed to trying to guess where a stock’s price is going in the future. The downside is that with Vega comes Theta, causing the position’s value to erode while you wait for volatility to kick in. This can be controlled to some degree, but that would need to be discussed in another article.

What Can Go Wrong?

If only everything behaved the way it should in theory.

Unfortunately, there are many things that can either jolt the market or quickly calm it down, causing traders to lose confidence in a volatility strategy. If you are accumulating Vega, most disruptions to the market can work in your favor if you capitalize on them fast enough. Remember that Implied Volatility has a strong tendency to return to the mean, so a sudden jump in volatility due to a one-time event may not last very long, but it can provide a great opportunity for profit. Since most disruptions that cause an increase in volatility also cause the overall stock market to drop, this can provide a pronounced sense of “I’m smarter than the rest of the world.”

On the other hand, when the market likes something and you are holding Vega, the opposite happens. This doesn’t mean the strategy is not working, but it is my belief that FOMO (Fear Of Missing Out) is one of the strongest motivators of trader behavior.

On a strong “up” day, a Vega-based strategy is likely to experience a temporary setback. While everyone at the party is high-fiving and celebrating their trading brilliance, you will need to remember that the daily ups and downs of the market have very little to do with whether people are meeting their long-term goals. It’s about consistency. Consistency requires a regular occurrence of something, and that is very difficult to find in stock price behavior.