Oil prices have been under pressure as the dollar soars. For many, they believe that the strength in the dollar is a major reason why oil will not be able to rally. Yet the truth is that while in recent years, the dollar-oil inverse correlation has been very tight, throughout history that has not always been the case. In fact, in the oil market, as well as other commodities, we may be at the verge of a total breakdown of what has been considered to be an almost dogmatic truth – which is as the dollar goes up commodities go down. The reason for that breakdown is the same reason commodities have become highly correlated to the dollar in recent years, and that is the impact of quantitative easing.

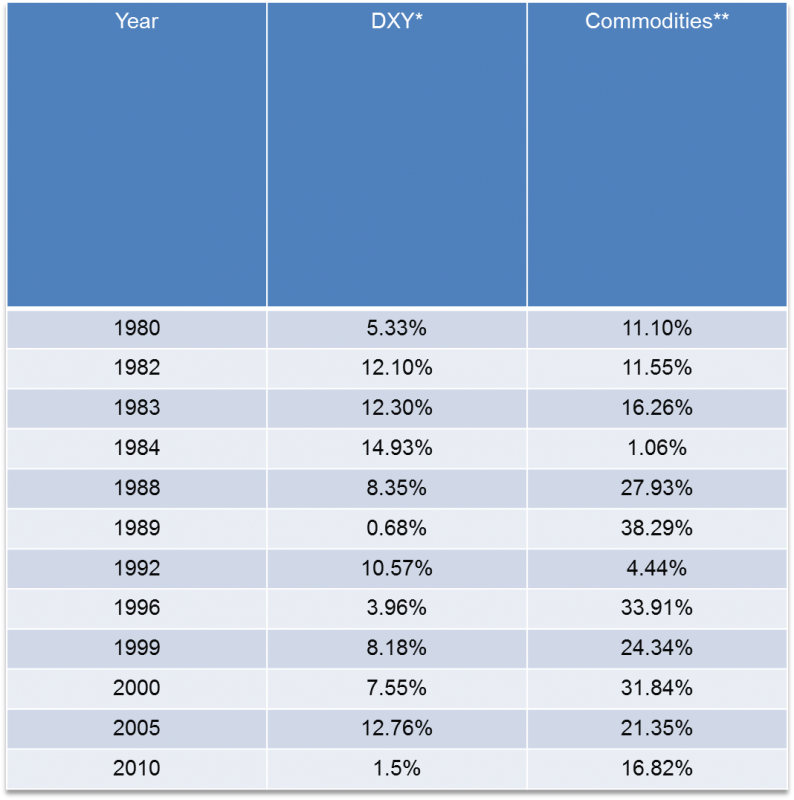

Let’s first break the myth that commodities and the dollar always go in opposite directions. There have been many times when commodities and the dollar have gone in the same direction and commodities actually outperformed the dollar (see chart below). When commodity demand is stronger domestically, or just so strong that price or exchange rate do not matter, this can occur and often has. The dollar has always been a major factor in the price of oil and other commodities because commodities are priced in dollars. But it is far from the only factor.

The exchange rate, and hence the value of the dollar, has historically had more influence on the price of oil due to the fact that in the nineties, the U.S. was the world’s largest oil importer and was importing almost 60% of its oil needs. But today U.S. net imports account for only 27% of the petroleum consumed, the lowest annual average since 1985, according to data provided by the Energy Information Administration (EIA). That huge drop in imports should make the price of oil less susceptible to currency market fluctuations.

A study by the European Central Bank actually studied the dollar-oil relationship and found that the strong negative correlation became clear in the early 2000’s, “while there was no such systematic correlation over the previous three decades.”

The 2008 and 2009 Panic

The dollar-oil correlation hit its zenith at the start of the financial crisis in 2008/2009 when the correlation ran near 60%. The reason for the high correlation was the strength or weakness of currencies was reflecting a shifting of risk assets to try to find a safe haven against what was an unfolding economic crisis.

Oil prices had been on a tear, the U.S. economy was expanding, and the explosive industrial revolution in China, as well as the growing strength of the European Union, had driven oil from $16.70 in the aftermath of the September 11th attacks to it’s $147.27 peak at the height of the economic crisis in 2008 – with the heat of the commodity buying frenzy.

While most of the early price movement was driven by supply and demand, a massive surge of over $97 a barrel from the lows in 2007 to the high in 2008 really was caused by panic as the wheels started to come off of the global economy.

Peak Oil?

Many were saying the reason why oil started its massive surge in 2007 was because we had hit “peak oil,” based on the theory that was taken from the work of M. King Hubbert, Shell Oil geophysicist, in a paper written in 1956. The theory was that as demand grew, and we produced more oil, the maximum rate of extraction of petroleum would be reached and the rate of production would then enter terminal decline. In 2007 there was talk of oil shortages. A book titled “Twilight in The Desert,” written by the late Matt Simmons raised fear that oil fields in Saudi Arabia, the world’s largest producer, had entered into decline.

The famous oilman T. Boone Pickens led that charge predicting that oil production had peaked and stated that with global oil production nearing 85 million barrels, “I don’t believe you can get it to any more than 84 million barrels. I don’t care what Abdullah, Putin, or anybody else says about oil reserves or production. I think they are on decline in the biggest oil fields in the world today, and I know what it’s like once you turn the corner and start declining. It’s a treadmill that you just can’t keep up with. If I’m right, we’re already at the peak. The price will have to go up.” Prices did go up, but the reason was not peak oil but something almost as ominous.

An Inverse Response

The real run on oil started and the historic high sensitivity on the oil-dollar relationship started in 2007 when the Federal Reserve and then Fed Chairman Ben Bernanke started to realize the depth of the financial crisis. In August 2007, the Federal Open Market Committee’s (FOMC) target for the federal funds rate was 5.25 percent, and as the economy started to deteriorate the Federal Reserve started to lower interest rates, even as Europe continued to raise them. This caused the dollar to tank and the massive buying of oil and other commodity assets to rise, acting as a hedge from the falling dollar’s value.

A Misunderstanding Arose

There was also buying as traders misinterpreted the move as a sign that the world supply of oil would tighten so much that big banking houses like Goldman Sachs would predict unending strength in demand from China and Europe, and that would drive oil as high as $200 a barrel, despite the problems in the U.S. economy. Many said that global economies had “decoupled” from the U.S. economy, and their problems would not hurt demand growth, even as the U.S. banking system started to fall apart.

Then Lehman’s Fall

Then in 2008, the Lehman Brothers bankruptcy stopped the world and oil, and the truth about what drove oil became apparent. It was not “peak oil”; it was a bubble created by money trying to find safety from a falling interest rate differential and the collapse of the U.S. dollar and banking system. Oil prices tanked and the demand for oil plummeted falling over 2-million barrels a day in an instant as credit and the global economy froze.

Then Comes QE

The only way to stimulate demand for oil at that point was to get the economy moving and try to raise confidence. On November 25, 2008, the Federal Reserve moved to try to mend the economy by announcing a move toward “quantitative easing,” a move that raised the correlation to an almost incestuous level. Let’s face it, the money printing by the Federal Reserve was the only demand growth hope that oil had going for it. On December 16, the program was formally launched after oil hit a low of $32.40 in that month.

Risk-On, Risk-Off Arrives

After that came the era of “risk-on, risk-off”. As economic hopes brightened, traders on “risk on” days would buy Euros, buy commodities, and sell the dollar. On “risk-off” days, they would do the opposite. Investment money was trading scared, as money was putting small parts of their body into the pool and pulling back until they eventually got used to the cold economic waters. The price of oil moved in lockstep, up on risk on days and down of risk off days, as it was clear that Federal Reserve actions and subsequent simulative actions by other Central banks were the only thing that prices and demand had going for it. Oil would ride the QE risk on-risk off move all the way back up to $114.83 a barrel in May of 2011.

Now the Fed is looking to raise interest rates as the rest of the world is going in the opposite direction. This is almost the exact opposite of the beginning of the financial crisis when the Fed started to lower rates, while Europe was raising them. With 63% of the global central banks raising rates, and the Fed in the U.S. signaling the same, the dollar has moved to a 13-year high and oil has fallen back to the lowest levels since when the Federal Reserve first initiated Quantitative Easing. While the move on oil is predictable from an exchange rate perspective, the question is: Will it be sustainable?

And Here We Are Today

Because even though in the short run, the dollar is weighing on oil prices, the fact that the Fed is normalizing rates should mean that the U.S. economy is finally starting to heal and will bode well for energy demand. Even in the economies that are struggling, we should see demand grow as more QE and lower interest rates will increase demand. If demand starts to spark, the price of oil will break away from its dollar value related change as the glut of oil starts to dry up.

The glut will dry up not only because demand will improve, but because the recent price fall caused a massive pullback in energy investment, which eventually took a toll on US production. With rig counts in the U.S. falling at a record pace, the U.S. output will fall later this year just as global demand starts to improve. This will start an oil demand price run that should bring prices back towards the $80 a barrel area.

#####

If you want to read more from Phil Flynn and PRICE Futures Group, please click here.