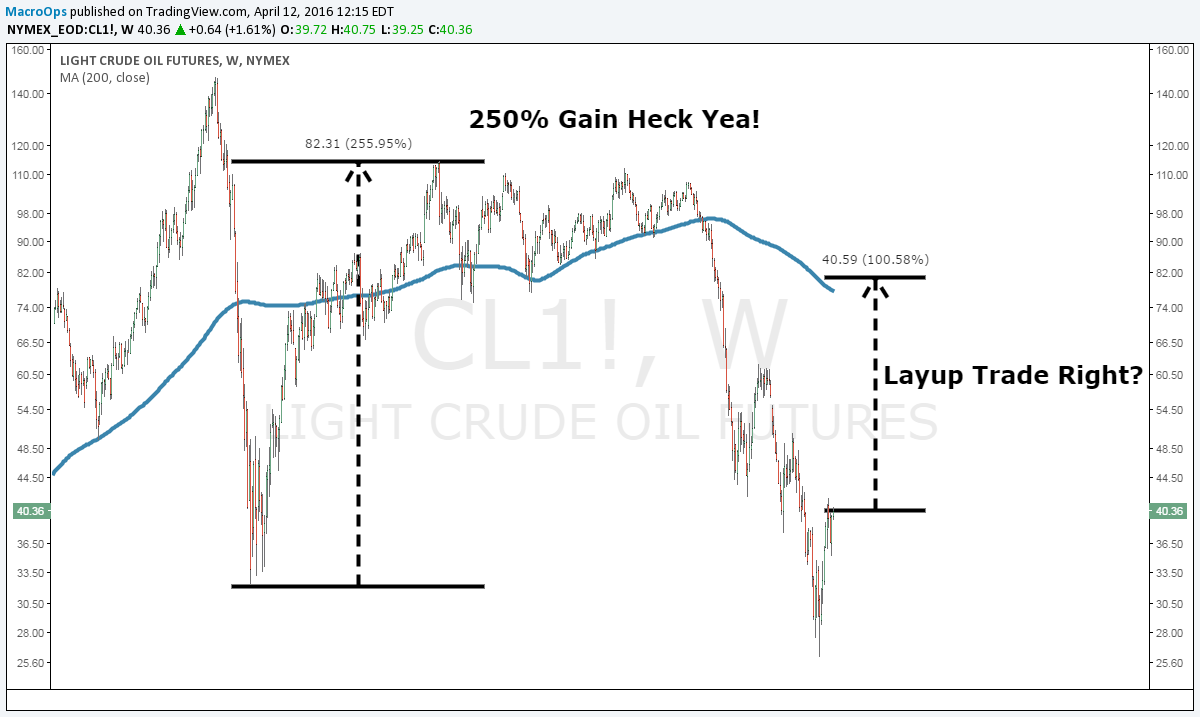

It’s funny, after the massive drop in oil prices over the last few years, it seems like everyone became an oil speculator all of a sudden. Loads of “investors” have been reaching out to our team at Macro Ops asking how best to play the oil rebound. They usually lead off with something like — “Oil is definitely going back to at least the 80’s. I mean look at 08’, oil had a 250% gain from the lows! I’m definitely going to double my money!”

Whoa there Boone Pickens. It’s not that simple.

Playing a commodity is not the same as playing a stock — even if you’re using an ETF. There are certain costs that need to be considered with this particular asset class. These costs ensure that your percentage gain on a move will likely be less than the actual gain in the underlying commodity.

Take a look at the popular oil ETF USO after the 2008 crash:

Yes… you are looking at the above chart correctly…

The reality is, USO only rose about 100% from 2008 lows — less than half the amount of physical oil.

Why? Well it’s because of a little something called “roll yield”.

Oil is a commodity, not a company. You don’t buy “shares” of oil. Instead, you buy futures contracts on the price of oil. (That is of course assuming you don’t have a tanker on your front lawn to store massive quantities of the physical stuff.) A futures contract is an agreement to buy or sell something in the future. If you’re unfamiliar with the concept of futures, check out our special report on them.

When you buy an ETF like USO, you’re basically paying someone to buy futures contracts for you. And a key feature of these contracts is that they expire. In the crude oil market, they expire every month. So if you’re long crude oil futures, you need to “roll” your exposure forward each month. You have to sell this month’s contract and buy next month’s to ensure continual long exposure. ETF’s like USO are convenient because they automatically roll these contracts for you.

Here’s where the extra costs come in though. The oil market’s futures curve is normally in contango. This means that contracts expiring further out in time cost more than those expiring sooner. This difference causes you to lose money every time you roll your contract to the next month. You’re constantly having to pay up for the next contract! This cost difference is due to “cost of carry” and interest.

If you were to buy physical oil, you would have to pay to store it somewhere. This is considered the “cost of carry”. Luckily with futures, you don’t have to store anything. But even so, when you buy a contract, this cost of carry is still reflected in the price. The further out the futures contract, the higher the cost of carry, and the higher the contract price.

The interest component works in a similar fashion. Buying futures contracts instead of physical oil is a LOT more capital efficient. A million dollars worth of physical oil will cost you a million dollars. But a million dollars worth of oil futures will only cost you about a hundred thousand dollars. It’s the power of leverage and it’s a great deal.

The cash you save can be used to earn interest on the side through something like treasury bills. But this advantage doesn’t come free because it’s once again reflected in the price of the futures contract you buy. The further out the futures contract, the more potential interest you can earn, and the higher the contract price.

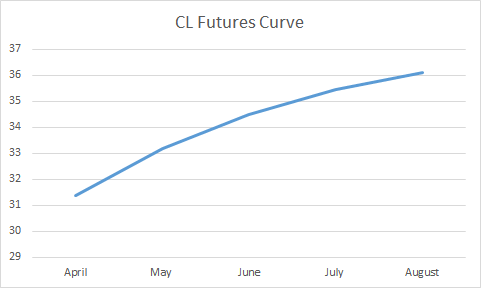

Below is an example of an oil futures curve:

In this example, you can see how April contracts trade for about $31.50, but May contracts trade around $33. When it comes time for USO to roll its exposure from April to May, it will have to sell its contracts at $31.50, and buy more expensive ones at $33.

Over time, the cost of rolling contracts kills returns. Investors basically have to pay a fee each month to keep their long exposure. This associated cost is why USO returned so much less than the actual price of oil after 2008. And the longer you hold an ETF like USO, the more you pay, which in the long run has a big effect on total returns.

The point is that you can’t treat USO like a stock. It doesn’t make sense to just buy and hold. This is especially true if the price of oil decides to move sideways for an extended period of time — your account will get eaten alive by roll costs. If you’re trying to speculate on oil, you’re be much better off using technical entry and exit points to hit a quick trend and get out.

USO is a great example of the need to thoroughly understand an instrument before you start trading it. Oil may be a good play to the upside, but make sure you play it the right way.

For more information about using futures to trade oil, please click here.