One of the new buzz words in the option industry is the vertical spread. Although they’ve been around for as long as option trading, popularity of the strategy has been on the rise due to historically challenging market volatility and a more sophisticated trading community.

Option buyers look to vertical spreads as a means of lowering their cost and risk of a particular trade. Similarly, option sellers seeking to collect premium as an income strategy might choose to implement vertical spreads to limit risk and lower margin. Nonetheless, we believe that in many cases trading vertical spreads might come with more baggage than benefits. Like any other strategy, there is a time and place for vertical spreads, but in my opinion they should not be the staple of a trading portfolio.

Vertical Option Spread Overview

By definition, a vertical spread is an option strategy in which a trader makes the simultaneous purchase and sale of two options of the same type and expiration dates, but different strike prices. A buyer of the spread would be purchasing the more expensive leg of the spread, which is the option with the strike price closest to the market, and then selling an option with a distant strike price. The seller of the spread would be selling the option with the most value (the one with a strike price in closest proximity to the current futures price), and then purchasing the cheaper option.

The term vertical describes the relationship between the option strike prices while inferring the components to the spread share the same underlying contract. A horizontal option spread, on the other hand, would consist of options in the same market and strike prices, but different expiration dates.

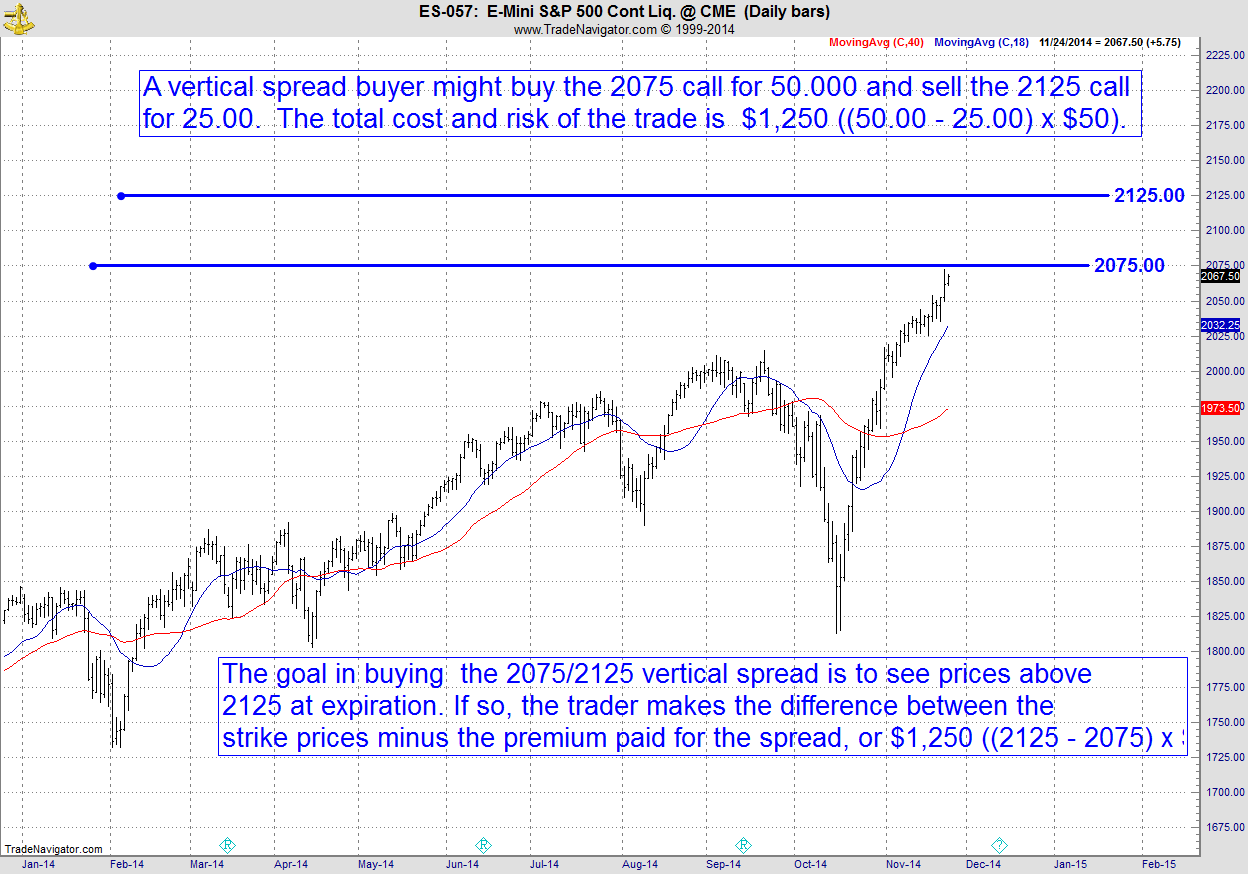

An example of a long vertical spread in the e-mini S&P 500 futures is the purchase of 2075 call and the sale of an 2125 call with roughly four months to expiration. Hypothetically, this particular vertical spread could have been bought for 25.00 points in premium, or $1,250 (25 x $50). Simply put, the buyer of the spread is willing to wager $1,250 on the prospects of the S&P 500 being above 2075 at expiration. However, the trader doubts prices will surpass 2125 and, therefore, is willing to reduce the cost of entry and risk by selling a call with a strike price at the noted level for $1,250 (or $25.00 in premium). Had the trader bought the 2075 call outright, the cost would have been about $2,500.

The sale of the 2125 call eliminates the profit potential above 2125. At the noted price, the spread is maxed out. Thus, selling a call to pay for a closer-to-the-money-call comes with the opportunity cost of limited profit potential. This is because at expiration, if prices are above 2125 the buyer of the vertical spread is making money on the 2075 call but losing the same amount on the 2125 call to create a “wash”.

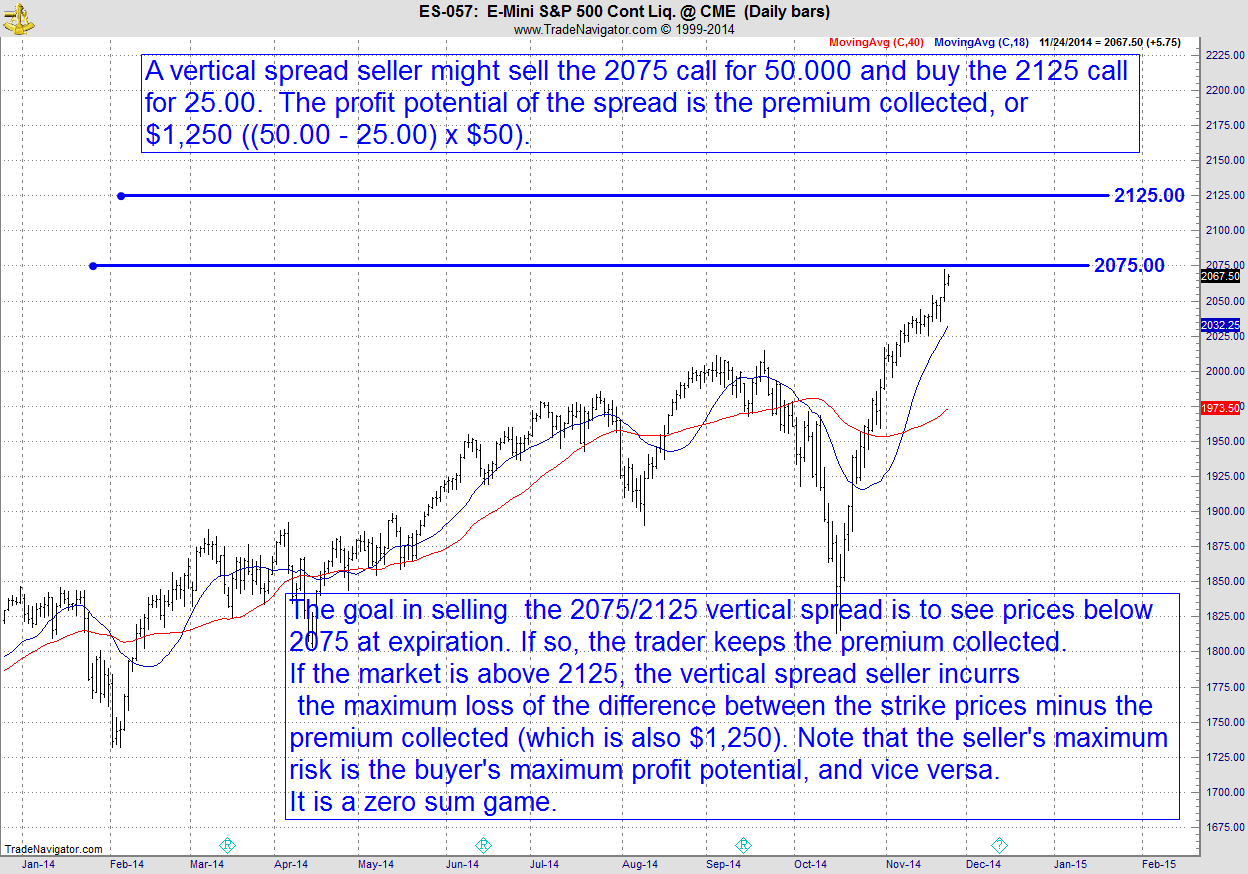

The seller of the spread is operating under the opposite premise. He believes the price of the S&P will be below 2075 at expiration, but is willing to purchase insurance to limit the loss should prices exceed 2125. In contrast to the previous trader who sold the 2125 call to finance the cost of the long 2075 call, the seller of the vertical spread purchases the 2125 call to the detriment of his profit potential in exchange for having peace of mind. Should the price exceed 2125, the vertical spread seller will not suffer additional losses because at expiration, for every point he loses on the short 2075 call, he is making back on the 2125 call.

Calculating the P&L of a Vertical Spread at Expiration

Calculating the profit of a vertical spread at expiration is relatively straight forward. The buyer of the spread has the potential to make the difference between the strike prices of the long and short options, minus the cost of entering the trade. For this to occur, the price of the underlying futures contract would have to be beyond the strike price of the sold option. Using the example above, the trader would be profitable by 25.00 before considering transaction costs, or $1,250 (25 x $50) points if the price of the S&P was above 2125 at expiration. This is figured by subtracting 2075 from 2125, and then factoring in the 25.00 points to purchase the vertical spread.

The seller of the spread faces the exact opposite payout profile; he stands to lose 25.00 points should the price be above 2125 at expiration. If the vertical spread expires worthless, he keeps the $1,250 originally collected (of course, this is the premium paid by the buyer). In summary, the maximum potential risk to the spread buyer, $1,250 in this example, is the maximum profit potential to the seller. Not surprisingly, the maximum possible payout to the buyer of the spread, $1,250 in this case, is the maximum loss to the seller. In other words, this is a zero sum game. For every trade there is a sinner and a loser with the exact opposite experience in regard to profit and loss. This example ignores transaction costs which must be added to the buyer’s cost, and subtracted from the seller’s premium collected.

Calculating Vertical Spread P&Ls before Expiration

Predicting the profit and loss of a vertical spread at any point before expiration is much more complicated; in fact, it is impossible. Before expiration, the spread profit or loss is determined by the widening or narrowing of the difference between the option values on the two legs of the spread. Because the premium of each of the options involved in the spreads are based on factors that cannot be quantified, such as demand, expectations of future volatility, emotion, and timing; the value of a vertical spread before expiration cannot be forecast. Any attempt at such is nothing more than an educated guess.

In addition, monitoring profit and loss of a vertical spread in real time can be frustrating. When trading vertical spread strategies, being right on market price is only half the battle. We’ll discuss this further in the following sections.

What are the benefits of trading long vertical spreads (buying the spread)?

The primary advantage to going long a vertical spread, as opposed to buying an outright option, is the luxury of positioning the trade closer to the current market price with reduced out of pocket expense. Going back to the aforementioned example, the trader saved about $1,250 in cost and risk by selling the 2125 call to pay for his long 2075 call. Simply put, the trader was able to purchase the 2075 call for $1,250, rather than the $2,500 price tag. Of course, there is an opportunity cost to getting a discount.

Rather than purchasing the 2075/2125 vertical spread, the trader could have opted to simply buy a call outright. We’ve already determined that the 2075 call would have come with a total cost and risk of $2,500 but it would have also been possible to purchase a call with a distant strike price to cut the cost to the desired $1,250. In this instance, the 2125 call could have been purchased for about 25.00 or $1,250. Thus, the trader faces the same risk and cost of the original vertical spread by simply purchasing the 2125 outright. As you can see, the trader would have sacrificed about 25 in strike price to achieve the same cost as the vertical spread. Naturally, the odds of the futures price being above 2075 at expiration are much greater than it being above 2125. Nevertheless, a buyer of a 2125 call would have potentially unlimited profit potential.

What are the pros of trading short vertical spreads (selling the spread)?

The most notable advantage to trading short vertical spreads is peace of mind. Unlike outright option sellers who face theoretically unlimited risk, vertical spread traders cap their risk at a predetermined level through the purchase of an option with a distant strike price. Accordingly, a short vertical spread provides traders with the assurance that regardless of a catastrophic event the total loss on the trade won’t exceed a certain level. In essence, the purchased option acts as insurance to the option seller, but as with most insurance policies, it is often more of a burden to a buyer than a benefit.

Trading naked short options outright might make more sense

On the surface, vertical spreads appear to offer traders the best of all worlds. They are limited risk, directional positions, with a built in hedge. Yet, there are two relatively unobvious draw-backs that sometimes make vertical spread trading a frustrating venture; delta and time.

If you aren’t familiar with delta, it is simply the pace at which the value of a particular option fluctuates relative to the underlying futures contract. For instance, if an option has a delta of .30 it will gain or lose 30% of a corresponding move in the futures market. To illustrate, an option with a delta of .40 and the S&P goes up 10.00 points, a call option should have increased in value by about 4.00. Of course, market pricing is based on emotion just as much as it is mathematics, so the relationship between option value and futures value isn’t always according to theory. In fact, there are times in which software identifies an option as having a low delta but market participants wildly bid prices up to unbelievably high prices that far exceed expectations based on the estimated option delta. Nonetheless, it is important to realize as a vertical spread trader at any point before expiration, volatility and time value can interfere with profitability of the trade. It is sometimes necessary to hold the position until expiration to achieve a worthwhile profit. This is particularly true during times of high volatility which has a tendency to neutralize the delta of the trade.

Beginner traders often learn the hard way that in highly volatile market conditions it is possible for a trader long a vertical call spread to fail to make gains, or even sustain a loss, despite the market moving in the desired direction. Using the previous example, this can happen if the value of the short 2125 call rises nearly as much as the value of the long 2075; some refer to this as a vertical spread handcuff. Such an occurrence is more common than most would think. This is because speculators often bid up the price of the “cheaper” options with distant strike prices due to affordability. The increased demand for these more affordable strikes often lead to higher percentage gains than options with strike prices closer to the market. Plainly, unless you are planning on holding the trade for a substantial amount of time, vertical spreads might not be the optimal strategy because you can be “trapped” into an unprofitable trade even if your original speculation was accurate.

Similarly, if time value erosion outpaces the benefits of the underlying market moving in the desired direction, a long vertical trader can find himself in a position in which he is losing money despite being “right” in price prediction.

The implications of vertical spreads for option sellers (as opposed to buyers) is even worse, the purchase of the “insurance” option typically encourages traders to execute trades in higher quantities due to lower margin requirements for vertical spreads relative to naked option selling. Many don’t notice it until it is too late, but they are often taking on more risk than would be the case selling naked options in lower quantities. Further, premium collectors typically sell options with strike prices closer to the market in order to make up for the premium paid for the protective option. Thus, the strategy of selling vertical spreads can sometimes become more dangerous that selling naked options!

The Bottom Line

Those trading outright calls and puts, will typically see much quicker profits and losses. They will also have the ability to trade in and out of positions more proactively than a vertical spread trader would. In summary, vertical spreads are a better “buy and hold” strategy for option traders while outright options are better suited for swing traders. Don’t fall into the fallacy that any type of strategy can be applied in all circumstances; there is a time and place for everything.

*There is substantial risk of loss in trading futures and options; it is not suitable for everyone.

Carley Garner is the Senior Strategist for DeCarley Trading, a division of Zaner, where she also works as a broker. She authors widely distributed e-newsletters; for your free subscription visit www.DeCarleyTrading.com. She has written four books, the latest is titled “Higher Probability Commodity Trading” (July 2016).