Unless you have had your head in the sand over the past week, thanks to the media, Greece is all we have been hearing about lately, from morning to night.

This has been in the making over the past 5 years and yet no real solution seems to be in sight, which is quite sad for the country as well as for the dream of a unified Europe.

Back in 2010, the problematic PIIGS (Portugal, Ireland, Italy, Greece and Spain) were all the talk, now it’s mostly centred on just Greece as the others have taken on the austerity pill by cutting back government spending, initiating economic growth policies and hence come away much stronger for it.

On the overall balance, Europe itself is also much stronger and a slow Eurozone recovery remains on track.

The question on most people’s minds is whether the default and exit of Greece from the Eurozone is likely to cause a major systemic risk resulting in another GFC style European crisis.

I generally keep away from predictions. Why? Because my success rate of economic predictions is fuzzy at best. All I can do is look at the facts and interpret them as best I can and form an opinion.

I have no idea if Greece will eventually leave the Eurozone, but what I do know is that Greece is unlikely to create any systemic risk throughout the rest of Europe. This time, it really is different.

In contrast to 2010 where many multi-national banks were exposed, now over 80% of outstanding Greek debt is held by foreign governments and will therefore not create any financial bank collapses. On top of that, Greece represents just 2% of the European economy.

Make no mistake, Greece is in trouble and the country has run out of money. A temporary closure of its banks and stock market is only there to protect itself from a run on its banks while the referendum is about to take place to decide on its future fate within the Eurozone.

For the past five years, its current government and economic policies have not resulted in any long-term solutions but continual short-term bandaging support by the International Monetary Fund (IMF).

Despite Greece being the first developed nation to default on its international debt, what most people do not know is that this is not the first time Greece has defaulted on its obligations.

In the modern era, there have been five other times it has defaulted, namely 1826, 1843, 1860, 1894 and 1932. Therefore, Greece has had a long history of not paying up.

Although the financial markets have dropped several percentage points over the past week due to Greece, on the overall scheme of things, it is relatively calm even though default has officially already taken place.

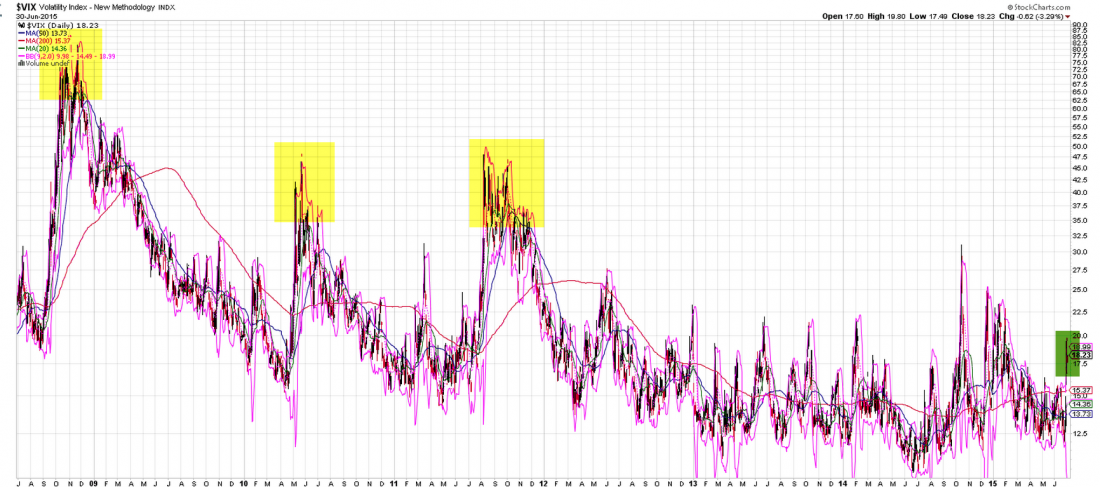

Most people analyse the S&P500 volatility index or better known as the VIX to see if any potential problems lurk around the corner. Even with the VIX spiking from 12 to over 18 (a 33% spike), it is still relatively low by historical standards. It measured over 80 in 2009 as shown in the chart below.

A much better but lesser-known indicator, the 2-year interest rate swap spreads are a much better guide to judge whether any systemic exists.

Currently, both the Eurozone and US 2-year swap spreads are well within normality and therefore indicate that financial markets are liquid and systemic risk is very low.

Going back to late 2008, 2010 and 2011, 2-year swap spreads spiked to well past 100, showing how nervous markets were at the time and liquidity had dried up. This time it really is different as no such risk is evident, with the Eurozone 2 year swap sitting at just below 40 and the US swaps sitting just above 20.

Also, the price of precious metals like gold and silver which financial markets usually flock to during financial crises are both at 5-year lows, another encouraging sign.

So whatever the outcome of Greece is, although painful for its citizens involved, it will unlikely create any meaningful long-term financial pain on a global scale.