In time of extreme volatility, investors often turn to options trading for portfolio protection, risk management, speculation, to generate potential income, and to enhance returns. If you are new to options, you’ll find they open up an exciting new realm of investment opportunities for you. Whether used alone or in conjunction with other market positions, options strategies can be complex and confusing. Hopefully I can help remove some of the mystery.

Options Terminology

There are two types of standard options: puts and calls. Call options represent the right to buy the underlying contract at a specified price (strike price) any time before a specified date. Put options represent the right to sell the underlying contract at a specified price (strike price) any time before a specified date.

While there are two basic types of options (puts and calls) there are also different styles of options depending on the product traded, with different expiration procedures. “American Style” options can be exercised at any time before the expiration date of the option. “European Style” options can only be exercised at the expiration of the option contract.

In most cases, the style of the option is irrelevant to the average trader, because options are tradable contacts. Both American Style and European Style options trade at U.S. exchanges. The type can vary by product. In either case, exchange-listed options are standardized contracts that can be bought and sold among different parties. Therefore, the holder (buyer) of an option can sell his/her contract to another party to offset the position anytime prior to expiration, thus realizing a profit or offsetting a loss, and eliminating the position from his or her books. Similarly, if one has a short options position, it can be bought back at any time before expiration. And actually, it often makes more sense financially to trade out of your options position, rather than exercise it before the expiration date, especially if there is a lot of time until expiration.

Let’s now define some basic options terms and concepts I will discuss further.

Premium – The cost of the option contract itself.

Strike Price – The price at which you can take a position in the underlying contract.

Underlying – The futures contract that the option is based on (i.e. March crude oil futures, December corn futures, June S&P futures, etc).

Exercise – The act of exchanging the option for a position in the underlying futures contract. The holder of an option exercises his right to buy (in the case of calls) or sell (in the case of puts) the underlying future at the strike price.

At the Money – If an option is at the money, the option’s strike price is the same as the underlying price. For example, if December gold futures are trading at $1,600 an ounce, the December gold 1600 puts and December gold 1600 calls are both at the money.

Out of the Money – If the option is out of the money, the option’s strike price is higher (for calls) or lower (for puts) than the underlying price. For example, if December crude futures are trading at $82/barrel, the December crude 85 calls and 78 puts are both out of the money.

In the Money – If the option is in the money, the strike price is lower (for calls) or higher (for puts) than the underlying price. For example, if the December e-mini S&P 500 futures contract is trading at $1,150, the December e-mini S&P 1125 calls and 1175 puts are both in the money. In-the-money options have intrinsic value, because they could be exercised, and the resulting futures position immediately offset in the futures market for profit.

Characteristics of Long Call Position

If you are long calls, the maximum profit potential is unlimited. For example, if you buy a December 1700 gold call, you have the right to be long December gold futures from $1,700 an oz no matter how high the price of gold goes. There is also no margin requirement, and your risk is defined. The most you can lose is the premium paid for the option, plus commissions and fees. So if gold futures are below the strike price at expiration, the option simply expires worthless and you do not exercise your right.

Long calls also give you leverage. For your December 1700 call, you are paying $5,500 (based on option prices around 9/28/11) for the right to control 100 troy ounces of gold. At a strike price of $1,700 per ounce, this represents $170,000 worth of gold.

However, time works against you. Each day that passes, the option loses a little bit of time value.

Characteristics of a Long Put Position

When you are long puts, you are anticipating the underlying market will decline. Your maximum profit potential is virtually unlimited. For example, if you buy a December crude oil 78 put, you have the right to be short futures from $78/barrel no matter how low crude goes. Your profit is only maxed out if the crude futures go to zero. There is also no margin requirement, and your risk is defined. The most you would lose is the premium paid, plus commissions and fees. If crude rallies, or finishes above the strike price at expiration, the option simply expires worthless and you do not exercise your right to the underlying position.

You also have added leverage with a long put. For your 78 put, you are paying $3,700 (based on option prices around 9/28/11) for the right to control 1,000 barrels of crude oil. At a strike price of $78 a barrel, this represents $78,000 worth of crude. However, time works against you. Each day that passes the option loses a little bit of time value.

Options Strategy #1: Portfolio Protection

I will go through some examples of how options can be used for portfolio protection, that is, as a risk-control tool against another market position. Please keep in mind, the prices and dollar amounts quoted are for example purposes only, and may not reflect current conditions. These are also not to be construed as specific trade recommendations.

Example: Buying Puts to Protect a Long Futures Position

Say you are long one December crude contract from $80, and are therefore exposed to downside risk. To help protect (or hedge) your portfolio, you buy one December crude 78 put for $3.70 (at a cost of $3,700 before commissions/fees).

You now have the right (but not the obligation) to sell one December futures contract at $78, thereby limiting your risk to $2 on the futures contract ($80 futures entry price less $78 option strike price), plus the $3.70 premium paid for the option (before commissions/fees). No matter how low the futures contract falls, as an options holder, you can sell one futures contract at $78 if you wish.

In buying a put in lieu of using a stop-loss order in the futures contract as a risk-management tool, you have protected yourself against possible “whipsaw” action that could take you out of your position.

Example: Buying Calls to Protect a Short Futures Position

In this example, you are short one December Treasury bond futures contract from 140-00, and are therefore exposed to upside risk. To help protect your portfolio, you decide to buy one December bond 141 call for three points (at a cost of $3,000 before commissions/fees).

You now have the right (but not the obligation) to buy one December bond futures contract at 141-00, thereby defining your risk to $1 on the futures contract plus the three points premium paid for the option (before commissions/fees). No matter what the underlying contract does, you can buy one futures contract at 141-00.

Options Strategy #2: Long Options for Speculation/Leverage

Options can also be used for speculation purposes, with or without any other positions. If you are bullish on a particular market, you can buy an options contract to establish a bias. Buying calls would establish a long bias, in the hope that if the underlying market rises, the call contract (or right to buy) will increase in value as well.

Or if you are bearish, buying puts would establish a short bias in the hope that if the underlying market falls, the put contract (or right to sell) will increase in value as well.

Options Pricing

So what determines an option’s value? In general, it is the perceived probability of it finishing in the money.

What determines the premium? The more time there is until expiration, the greater the chance that the option could finish in the money. Therefore, the price of the option will be higher. You have more time to be right, so to speak, so you pay more for that right.

The relationship of the strike price to the underlying is also an important factor in options pricing. For example, if crude oil futures are trading at $80, the right to buy crude at $85 is worth more than the right to buy crude at $90, because the chance of crude finishing above $85 is greater than the chance of it finishing above $90 at expiration. It would have to make a much larger move ($10 versus $5) in the same timeframe, to get to $90.

Volatility is also an important factor related to options pricing. As market participants anticipate large price swings, the chances of an option finishing in the money theoretically goes up, as will its value. Note that this is anticipated volatility; we are interested in what the underlying will do between now and expiration, not what happened in the past.

You can also look at an options pricing in relation to the basic fundamental forces of supply and demand. Ultimately the contract is worth whatever someone will pay for it. As realized market volatility increases, investors often grow weary from the rapid changes in their portfolios’ values. In times of increased volatility, they will often buy options to hedge their positions as well as for their defined-risk speculative characteristics. This increase in option demand causes an increase in option prices in general.

Options Strategy #3: Long Calls for Speculation

Let’s go over another example using long calls for speculation, and how to determine which calls to use with these pricing tenets in mind. Say December Silver is trading at $30/oz, and you believe the price will go up. So, you consider buying either the December silver 30 calls or the December silver 36 calls.

The December silver 30 calls (at the money) are trading at $3.

The December silver 36 calls (out of the money) are trading at $1.

Note that the at-the-money calls are more expensive than the out-of-the-money calls. The right to buy silver at $30/oz is more expensive than at $36/oz because there is a greater chance silver will rise above $30 than $36 before expiration. If you think about it, if they were priced the same, then why would anyone buy the $36 call?

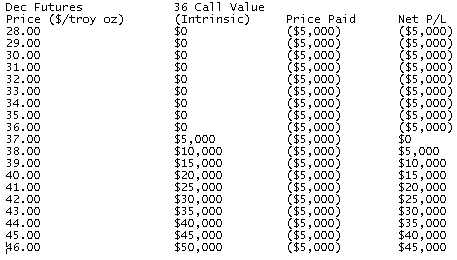

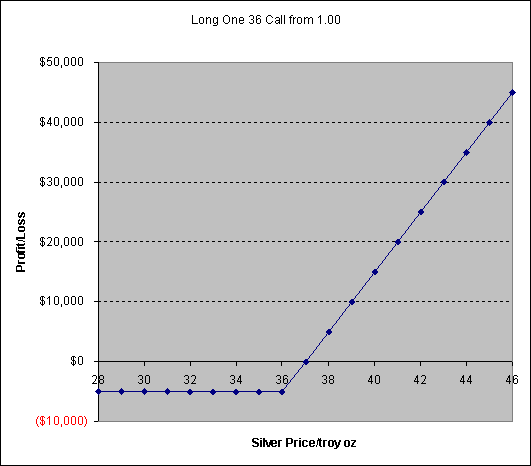

For the sake of this example, you decide you don’t want to pay for the higher-priced option, and buy one December silver 36 call at $1 ($5,000 before commissions and fees). You now have the right (but not the obligation) to buy one December silver futures contract at $36 before the option expires (in this example, on November 22). In exchange for this right, you would pay approximately $5,000 (one silver future = 5,000 troy oz) plus commissions and fees.

Tables 1 and 2 illustrate how various option values change based on the underlying market’s price, and how your potential profit or loss would be impacted.

Table 1: Profit/Loss at Expiration (Exclusive of Commissions)

Table 2: Long Silver36 Call for $1.00

Options Value

The value of the option is the intrinsic value plus the time value. Because the option in this case is out of the money, its intrinsic value is zero (all of its value is time value). With each day that passes, the time value drops, until expiration, when the time value is zero. As the price of the underlying market moves, the value of the option changes. The amount the value of the option changes in relation to the movement of the underlying is known as its delta.

As time passes, the option’s value approaches pure intrinsic value.

Options Strategy #4: Long Puts for Speculation

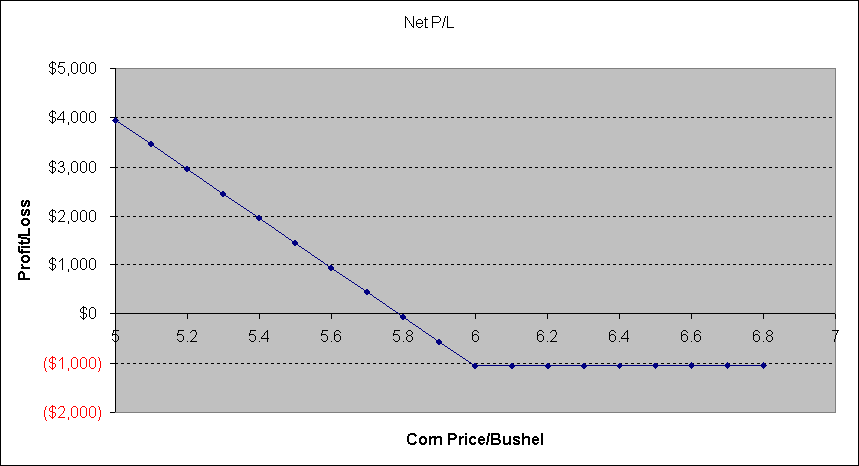

Let’s now look at using long puts for speculation. Let’s say the price of December corn is trading at $6.30/bushel. You believe the price of corn will fall, so you consider buying either the December corn 6.30 puts, or the December corn 6.00 puts.

The December corn 6.30 puts (at the money) are trading at 35 cents

The March crude 6.00 puts (out of the money) are trading at 21 cents

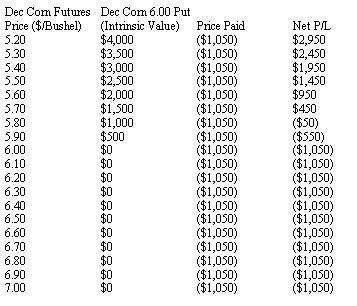

You decide you want the cheaper option, buy one December corn 6.00 put and pay 21 cents ($1,050 before commissions and fees). You now have the right (but not the obligation) to sell one December corn futures contract at 6.00 before the option expires (in this case, on November 25.) In exchange for this right, you pay $1,050, plus any commissions and fees. Tables 3 and 4 illustrate this scenario.

Table 3: Profit/Loss at Expiration

Table 4: Long Corn 6.00 put for 0.21

Options Strategy #5: Using Options to Generate Income

There are options strategies that can be used as potential income-generating tools. I’ll discuss one of these, selling (writing) a call against a long futures position (covered call).

Example: Covered Call

Say you are long a December crude oil futures contract from $80. You sell one December crude $90 call at $2.30, and collect the premium ($2,300 before commissions and fees). You are now obligated to sell one crude futures contract at $90 to the holder (buyer) of the option if the holder exercises his or her right to the underlying. In turn, you keep the premium, whether or not the option is exercised.

Let’s look at some scenarios at expiration based on this strategy. With the price of the crude oil futures trading above the option’s strike price, the option holder

exercises his or her option, and forces you to sell one futures contract at $90. This offsets your long futures position. You keep the premium of $2,300, and realize $10,000 on the futures (long from $80 and offset at $90). Your profit is capped at $12,300 at expiration, less commissions and fees.

Now, let’s say the price of crude oil futures are trading below the strike price. The option expires worthless. You keep the premium of $2,300, and your profit on the futures is determined by where you offset in the market, less commissions and fees.

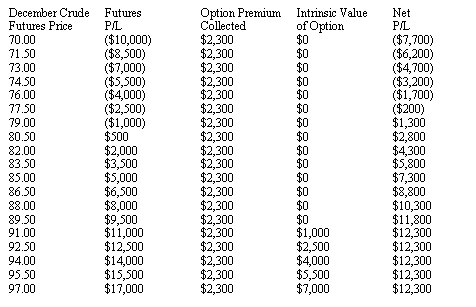

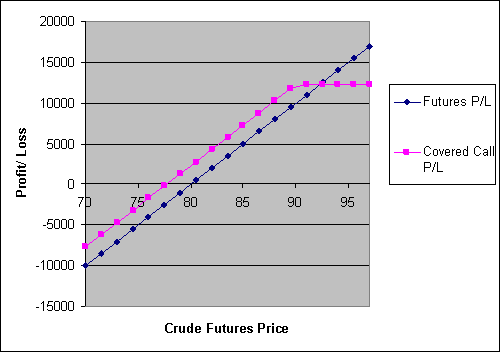

Tables 5 and 6 show various profit and loss calculations based on this scenario, and how the change in the price of crude oil futures impacts your outcome. The blue line in Table 6 represents the profit or loss for an uncovered futures position, while the pink line represents the profit or loss for a long futures position combined with a short 90 call. In the covered call scenario, you can see that your profit potential is capped, but the trade off is that you can get additional income from selling the call, as reflected in the upward shift of the pink line (long futures, short call) from the blue line (long futures only).

Table 5: Long Crude Futures from $80, Short $90 Call at $2.30 at Expiration

Table 6: Profit and Loss at Expiration

A covered put situation is similar to the covered call scenario, with the difference being that your risk is to the upside, rather than the downside. In a covered put, you would sell a futures contract and sell a put. The buyer of the put would have the right to sell you a futures contract at the strike price of the put, obligating you to buy one futures contract if that individual chooses to exercise the option. Your profit potential on the short futures position would be capped as futures move below the strike price of the put you sold. You would collect the premium from selling the option no matter what price the contract finished at. Your upside risk is still unlimited on the short futures position.

I’ve just covered some of the basic concepts about options that I feel new options traders should know, but I’ve really just scratched the surface. There is a lot more to learn about options, including other strategies such as naked options, straddles and strangles. I invite you to explore the world of options further, and to contact me with any questions you might have about futures or options trading, or the markets.

Matt Krupski is a Senior Market Strategist with MF Global’s Individual Futures Trading division. You can contact him at 877-847-3034 or via email at mkrupski@mfglobal.com if you have questions on this topic or to discuss specific trading strategies for your unique situation.

Futures trading involves substantial risk of loss and is not suitable for all investors. Past performance is not necessarily indicative of future results.

(c) 2011 MF Global Ltd. 141 W. Jackson Blvd. 1400-A, Chicago IL 60604.