Futures traders might find it helpful to think outside of the box when it comes to margin.

Although, doing so, will mean straying from the comfort of using black and white figures by crossing into the ambiguity of option trading.

Unlike futures trading in which there is a specified, and relatively static, dollar amount in required margin–option traders face dynamic margin requirements which are almost always at a discount to the outright futures margin. Similarly, futures traders can use long and short options to lower their requirements, and hedge their risk.

THE BASICS

Before we can discuss the intricacies of margin, let’s make sure we all understand the concept.

Margin is simply a specified amount of funds stipulated by the exchange and required to be held in a brokerage account to trade in a futures market. In essence, it is a good faith deposit that assures the exchange you will have the ability to meet your obligations of loss. More importantly, others will be able to meet their commitments, enabling you to profit from correct speculation. Without margin, the exchanges would not guarantee each transaction in the manner they currently do.

DIFFERENT TYPES

For the purpose of this discussion, we’ll ignore exceptions such as discounts for day traders and hedgers. However, it is important to recognize the difference between “initial margin” and the “maintenance margin.” All generic references to margin refer to the initial margin, which is the amount of money that must be on deposit to enter a trade. The initial margin is typically a small percentage of the contract’s actual value. Maintenance margin, on the other hand, is the amount of money that must be in an account to hold an existing position. Maintenance margin will always be lower than the initial margin, and is typically about 70% of initial.

WHAT IS DELTA?

Delta is, in my opinion, the most useful of the infamous option Greeks. It simply gives traders an idea of what the percentage change in a particular option, or option position, will be relative to a change in the underlying futures contract. The delta will be a value between 1 and 0, with 1 being equivalent to a futures contract (or 100%) and 0 being a worthless option.

For example, if an option has a delta of 50, or 50%, it suggests that for every point the futures market moves the option will move half of that amount. In general, the higher the delta the higher the risk and many cases the higher the margin.

USE DELTA TO LOWER MARGIN

A trader holding a futures contract, which has a delta of 1, can reduce margin and risk by lowering the delta with options. This can be done through the purchase or sale of antagonistic calls and puts. For instance, a trader long a futures contract could buy a put, sell a call, or both. They might also choose to do any variation of multiples.

The purchase of a put acts as an insurance policy to the futures contract; it limits the risk absolutely to the amount of the premium paid and the difference between the strike price and the entry price of the futures contact. In the process, it decreases the delta of the position because the put (disregarding time) stands to make money as the market drops which is opposite of the long futures position.

The sale of a call option against a futures contract, known as a covered call, doesn’t limit the risk of the futures contract but the premium collected does act as a buffer against losses on the futures contract if the market drops. It also adds cash to the account that can be applied toward margin and it decreases the delta of the trade because the short call benefits in a falling market. Gains on the short call help to offset some of the pain caused by being long a futures contract in a declining market. Accordingly, the exchange offers a margin break.

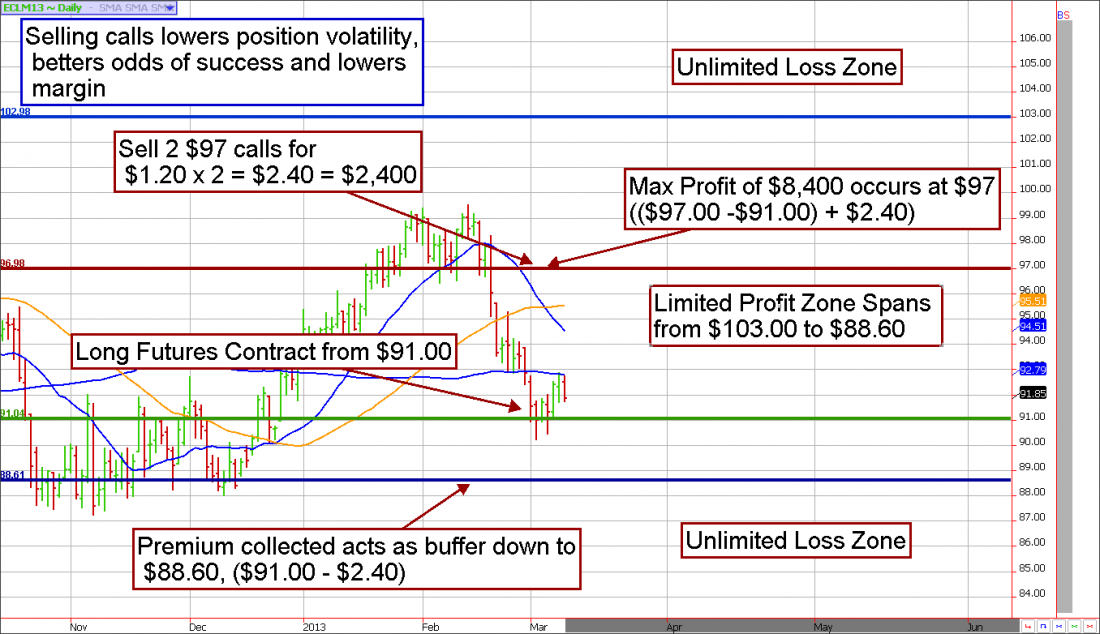

Specifically, a trader in March might have gone long a June crude oil futures contract from $91.00. Alone, this position faces a margin requirement of $4,950, but it would have been possible to sell two call options at a strike of $97.00 for $1.20. Because two call options are being sold, the total premium collected would have been $2.40 before accounting for commissions and fees; this is equivalent to $2,400 because crude oil is worth $10 per penny to a trader. The delta of the $97 calls at the time was 25; because the short calls work against the futures contract the delta of the overall position is reduced from 1 to .50, figured by subtracting the option delta from the futures delta (1 -( .25 x 2)). In the new arrangement, the trader’s position will move about half as much as the underlying futures contract.

Not only did this trader lower their delta and trade risk, but the premium they collected is used toward lowering the overall margin requirement. In this particular example, the margin would be reduced from just under $5,000 to just over $2,000 while the risk of loss on the trade is shifted from the futures entry price of $91.00 to $88.60 compliments of the premium collected acting as a buffer against futures contract losses.

*There is substantial risk of loss in trading futures and options.

#####

To learn more about Carley Garner and DeCarley Trading, please click here.