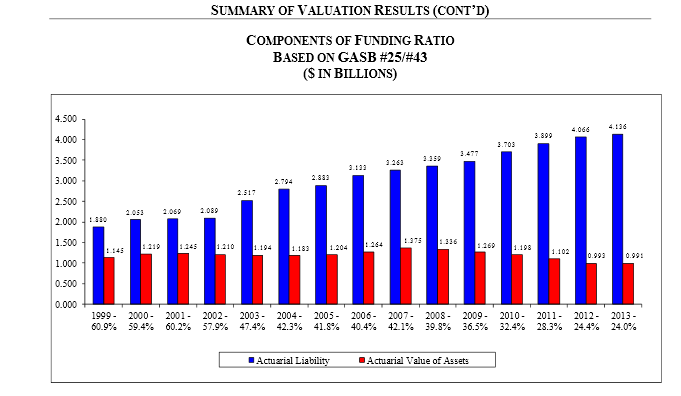

Below is a chart that a friend of mine brought to my attention (thanks CH) from the Fireman’s Annuity and Benefit Fund of Chicago, which is one of Chicago’s pension funds. The problem of unfunded liabilities shown in this chart is stark, with liabilities going up and the market value of assets trending slightly lower. In fact, the market value of assets is below the level of 1999. And these really aren’t small numbers; the gap is nearly $3 billion.

Now I don’t mean to say that all pensions are just like this one. The Chicago Public School retirement system is slightly better than 50% funded. While the pension problems of many municipalities are well known, the broader issue is how hard it is for the population as a whole when considering retirement needs. For example, Grant Williams posted a note for Business Insiders, “Most Important Charts with this comparison: Amount of interest income on $10m invested in Two-Year Treasury Notes: June 2007 $50,500 and January 2015, $5,400.”

Consider what happens to the older generations when facing the reality that their retirement nest egg hasn’t been inflated away, but has been deflated away in terms of lack of investment income. Of course, they tend to keep working at any job they can get is my suspicion. This theory is bolstered by data from the St Louis Fed labor participation rates. We all are reminded how low the total labor participation rate is, but note that since 2007, the participation rate for 20-24 year olds went from 75% to 70%, while for those 55 and older remained more or less constant at 40%, and for those over 65, it rose from around 21.5% to 23.9% (data for those 65 and older only goes back to 2009).

How is the younger generation affected? They probably say, “Holy moly, I better get an education; not many great jobs out there and I better have the skill set for the new economy.”

So they take on debt to fund higher education. That’s probably part of the reason for the decline in the youth labor participation rate. But once they’re out of school, they are saddled with debt and facing competition not only from their peers, but from the older generation. In the aggregate, they don’t form families as quickly and aren’t inclined to become first-time home buyers. So, this group, which tends to have a higher propensity to spend, is restrained due to debt burdens, thereby holding economic growth down, which, in turn, keeps interest rates low, which, of course, compresses investment income for retirees, so they keep working. It’s a circular problem. The Fed, knowing of the demographic bulge of the older generation and unfunded retirement plans of one sort or another, desperately tries to keep equities levitating. When Bernanke says he’s not the one that threw seniors under the bus, it’s probably true…

If not for the overhang of national (and global) debt, the Fed wouldn’t be as compelled to continue to try to boost equities. The good news from the point of view of the US is that for the household sector, mortgage and consumer credit-card debt have been well under control since the crisis. What is not under control, of course, is student debt. Let’s consider these categories in turn.

From the Fed’s latest Z.1 report, Mortgage Debt has declined every year since 2007, from $10.6T to $9.4T. Consumer Credit stands at $3.3T. Revolving Consumer Credit (i.e. credit cards, a subset of the total) has been well behaved, going from $840 billion in 2010 to $889B in 2014, an increase of less than 6% over 4 years, or about 1.5% per year. But total Consumer Credit went from $2.65 trillion in 2010 to $3.32T, an increase of 25%. And that, my friends, reflects the student debt problem, which is currently at $1.2 trillion. There’s a substitution of student debt for other types of debt, collateralized not with physical property, but with supposed knowledge.

The delinquency rate is near an all-time high or around 33% (more than 5 days late), and around 17% for over one month late. Actually, data from the NY Fed suggests that nearly half of all student loans are either in deferral or a forbearance period. Given that the Federal Gov’t either owns or guarantees around 90% of these loans, I can’t quite decide whether we should consider this issue as a Federal Stimulus Program, whereby money flows to universities and isn’t paid back, or as an anchor on economic growth. It’s the latter of course, but what if this amount could just be wiped off the books? It would be a transfer of debt from the educated youth of the country to the public debt. (What’s another trillion given the $18T already outstanding?) It would probably unleash a wave of spending and economic activity that would spur increases in inflation, and thus interest rates, boosting the incomes of retirees and adding to the aggregate amount of taxes collected.

Certainly there are huge problems with the idea of a student-loan debt jubilee. But this is a large problem, and if government actions radically change the trajectory of student debt, it could have a big economic impact.

#####

For more timley trading ideas, please check out our daily Markets on the Move section.